Plastic traces were discovered in the brains of 54 individuals in the United States. However, specialists indicate that not enough information exists regarding the health impacts or prevalence of microplastics within the brain.

A recent study has revealed that micro- and nanoplastics detected in human brains and livers have risen from 2016 to 2024.

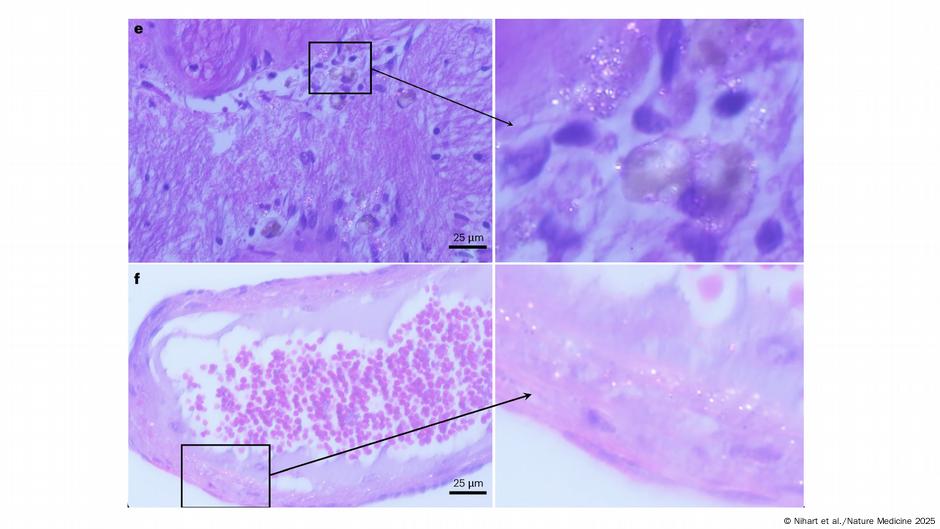

The study, published in Nature Medicine, Discovered that brain tissue taken from human corpses in 2016 had significantly greater amounts of plastic particles compared to both liver and kidney samples.

Micro and nanoplastics are minuscule — usually measuring around 200 nanometers in length, and significantly smaller than a human cell.

An analysis performed on cadavers from 2024 found even higher amounts in brain and liver tissues compared to 2016.

"We hypothesize that most of these plastics are not from recent exposure, but are extremely old degradation products. [This] highlights the need for more comprehensive strategies encompassing environmental policy and human health," study author Marcus Garcia at the University of New Mexico, US, told .

However, there is "as yet no strong evidence of any health effects [of nanoplastics in the brain]," said Oliver Jones, an expert in biological chemistry at the University of Melbourne, Australia, who was not involved in the study.

"The authors only [tested] 52 samples in total. There is not enough data to make firm conclusions on the occurrence of microplastics in New Mexico, let alone globally," Jones said.

Researchers are unclear about how microplastics negatively impact brain health.

Plastics inundate our planet — found in households, the very air we inhale, the meals we consume, and the containers we use for drinking.

Microplastics are bits of broken-down plastic. Most often, the Plastics get into our bodies via consumption or breathing. They have been present in human organs for many years, however, their impact on health is only now starting to be recorded.

Some findings suggest that the buildup of microplastics, particularly within vital organs such as the liver, may disrupt typical physiological processes.

The data from the research also revealed that the concentration of microplastics was greater in the brains of 12 individuals suffering from dementia.

The authors, however, state that this connection is merely correlational and does not establish that microplastics lead to dementia. Further investigation is necessary to determine whether, or in what manner, the buildup of microplastics in the brain adversely affects health—similarly to the way more research is required for the rest of the body.

"Concrete proof connecting the buildup of microplastics to particular human illnesses or health effects is not yet available," Garcia stated.

Determining a cause-and-effect link with dementia would necessitate comprehensive studies to discern whether or how microplastics play a role in the onset or advancement of such neurologic disorders.

Research might exaggerate the buildup of microplastics.

Jones likewise advised being cautious when drawing conclusions from the findings of the research.

He mentioned that it's not feasible to generalize the findings from this limited study to populations worldwide. The research might have exaggerated the levels of microplastics found in the brain tissues of the deceased individuals as well.

Jones additionally mentioned that the primary analytical technique employed to quantify plastics tends to produce inaccurate outcomes since “fats [a major component of the brain] yield identical compounds as polyethylene [the predominant type of plastic reportedly found],” and he raised doubts about potential plastic contamination originating either from the lab or during the initial autopsy process.

" Plastic pollution can be found virtually anywhere. ", how can we ensure that any detected particles truly indicate that plastics are penetrating membranes within the human body, rather than being mere contaminants?" Jones stated.

In what ways can microplastics enter or exit the brain?

The researchers suggest that their study introduces new queries regarding the possible effects of microplastics on brain health and whether these particles can be eliminated.

"The primary question revolves around comprehending the processes responsible for microplastic buildup in the brain — how these particles infiltrate it and which biological pathways they engage," explained Garcia.

Scientists have not yet determined whether our bodies can naturally eliminate microplastics from the brain and other organs. Additionally, it remains uncertain if there are processes that could assist in breaking down these microplastics within the body.

"Definitely, additional research would be necessary to determine whether this is feasible at all. It remains unclear if microplastics or any other particles could persist within the brain or if they might be eliminated by the body. Once again, further investigation would be required to explore this," stated Jones.

Edited by: Matthew Ward Agius

Primary source:

Accumulation of Microplastics in Deceased Individuals' Brains, Nature Medicine, February 2025 https://www.nature.com/articles/s41591-024-03453-1

Author: Fred Schwaller